We explain what we would like to see from the participants at this year’s climate-change event in Egypt.

Key points

- COP27 is currently being hosted in Egypt with the three main goals being to agree collective plans around climate-change mitigation, adaptation and finance.

- Despite 196 governments agreeing at COP21 in Paris in 2015 to limit temperature rises to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and preferably to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius, carbon emissions continue to rise.

- As part of the Paris Agreement at COP21 in 2015, developed countries committed to providing developing countries with US$100bn per annum to manage climate change.

- This sum has yet to be met, but it may prove insignificant compared to what more may be required to finance the global energy transition

It has been 27 years since countries and global organisations first met at the United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference, or COP for short, to collectively discuss how to bring about carbon-emission reductions. To many observers, this might be construed as 27 years of talking but a relative dearth of meaningful action. In this blog, we reveal our wish list of commitments and pledges we and our clients would like to see from governments and companies at COP27.

COP27 is being hosted in Egypt this year from 6 to 18 November. It is significant that an African country is hosting the latest COP, given that the continent is at the sharp end in terms of its vulnerability to the consequences of climate change. In addition, Egypt is responsible for around 13% of Africa’s carbon footprint while having only 7.6% of the population, so there is pressure on the country to deliver in relation to its own goals as well as attempting to re-energise the issue globally.

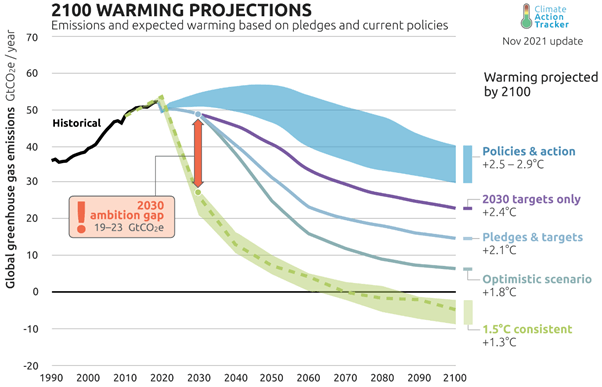

The global context for COP27 is that despite 196 governments agreeing at COP21 in Paris in 2015 to limit temperature rises to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and preferably to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius, carbon emissions rose from 35 gigatons (Gt) in 2016 to 37 Gt prior to the Covid pandemic. They are currently projected to be around 19-23 Gt higher than required under pathways consistent with the 1.5-degree Celsius outcome even if existing 2030 targets are hit. The graphic below highlights the magnitude of the challenge.

Source: Climate Action Tracker, November 2021 update. (One GtC02e equals one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide).

All COPs are important as they are an opportunity for countries to negotiate and work through disagreements. The three main goals for COP27 are mitigation, adaptation and finance. We look at each one below and set out our expectations.

Mitigation

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted a global energy crisis that has been in the making for at least a decade. While the current crisis is likely to be a long-term accelerant for climate action as countries seek to invest in new energy supplies which are typically cleaner, the scramble for energy security has led to a near-term resurgence in fossil-fuel power.

At the last event, COP26 in Glasgow, countries committed to resubmit enhanced emission-cutting pledges. At COP27, we hope that countries will reiterate their long-term commitments and strengthen their medium-term commitments to help reduce dependency upon an antiquated energy system that can be broadly characterised as one of monopoly, pollution and geopolitical vulnerability.

This will, we hope, arrive in the shape of some updated nationally determined contributions to global emission reductions and increased commitments to renewable energy as part of the energy mix. The countries likely to update their plans include Chile, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Vietnam, which collectively represent around 4% of global emissions.[1]

Adaptation

The role of adaptation has gained prominence in the face of the increasing frequency of natural catastrophes that are being linked to climate change. Examples such as the recent floods in Pakistan, hurricanes in the US, wildfires in Australia, the US, Europe and even the UK, have focused the mind that building resiliency into our global systems is becoming a prerequisite, particularly in the face of increasing global emissions. The UN estimates that typically only around 20% of climate change-related finance goes towards adaptation as it is more difficult to generate a return from such activity than from mitigation projects like renewable energy.[2] It is not anticipated that there will be any concrete outcomes on adaptation but, instead, that countries will continue to enhance their understanding of climate adaptation and flesh out principles and targets on how it can be achieved. This foundation building is important to enable meaningful progress in 2023.

Finance

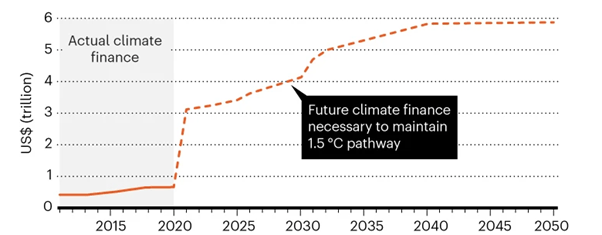

There are two components within financing: first, climate finance, and second, loss and damage. As part of the Paris Agreement in 2015, developed countries committed to providing developing countries with US$100bn per annum to manage climate change. This transfer was agreed owing to the reality that the bulk of the cumulative cause of climate change rested with developed nations. Since the Paris Agreement, this target has not been met. In 2021, it was closest to being achieved when US$83bn was raised through public and private sources. The bigger picture here is that the US$100bn is insignificant compared to what may be required to finance the global energy transition as estimated in the chart below.[3]

Climate finance (actual and forecast requirements)

Source: Climate Policy Initiative, 2020

At COP27, developing countries will be seeking to reapply the pressure on developed countries to deliver, and we would like to see the beginnings of an agreement between developed countries as to who will provide what, to whom, and when. These nascent plans could then be finalised at COP28 in 2023.

This clarity will help developing countries to plan capital expenditure for either mitigation or adaptation initiatives which are so desperately needed if the Paris Agreement’s goal to limit temperature rises to 1.5 degrees Celsius is to be realised. Given the near-term geopolitical and inflationary headwinds facing much of the developed world, we fear that enthusiasm for this process is likely to be somewhat muted at COP27.

The issue of loss and damage has become a contentious issue in the last few years with no consensus or enforceable plan. Loss and damage differ from mitigation and adaptation, in that they seek to provide help to people after they have suffered climate-related events, while mitigation works on preventing it and adaptation on minimising it.

Despite developed nations having caused the issue of climate change, national-level political cycles and self-interests have served to deter developed world governments from being interested in transferring sufficient wealth or paying compensation. Given the increasingly deglobalised world and political challenges at a national level in developed markets, we fear there is a high probability that insufficient progress will be made in this area at COP27, as developed countries seek to protect themselves from extra liabilities against a government budget-constrained backdrop. At best, we hope that some meaningful pledges will be made that can serve to help in the fight against the biggest existential threat we face.

[1] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/18/chairs-summary-of-the-major-economies-forum-on-energy-and-climate-held-by-president-joe-biden/

[2] https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/raising-ambition/climate-finance

[3] https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02846-3

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Newton manages a variety of investment strategies. How ESG considerations are assessed or integrated into Newton’s strategies depends on the asset classes and/or the particular strategy involved. ESG may not be considered for each individual investment and, where ESG is considered, other attributes of an investment may outweigh ESG considerations when making investment decisions. ESG considerations do not form part of the research process for Newton's small cap and multi-asset solutions strategies.

Important information

This material is for Australian wholesale clients only and is not intended for distribution to, nor should it be relied upon by, retail clients. This information has not been prepared to take into account the investment objectives, financial objectives or particular needs of any particular person. Before making an investment decision you should carefully consider, with or without the assistance of a financial adviser, whether such an investment strategy is appropriate in light of your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances.

Newton Investment Management Limited is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence in respect of the financial services it provides to wholesale clients in Australia and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the UK under UK laws, which differ from Australian laws.

Newton Investment Management Limited (Newton) is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN. Newton is providing financial services to wholesale clients in Australia in reliance on ASIC Corporations (Repeal and Transitional) Instrument 2016/396, a copy of which is on the website of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, www.asic.gov.au. The instrument exempts entities that are authorised and regulated in the UK by the FCA, such as Newton, from the need to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act 2001 for certain financial services provided to Australian wholesale clients on certain conditions. Financial services provided by Newton are regulated by the FCA under the laws and regulatory requirements of the United Kingdom, which are different to the laws applying in Australia.

Comments