Energy security and decarbonisation: are they mutually exclusive?

Key points

- The European energy crisis, which has been exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has been years in the making, and has highlighted the vulnerability of European energy systems.

- As nations scramble for energy, there are concerns of what this may mean for the energy transition.

- We believe that over the medium and long term, concerns around energy security are likely to accelerate the shift to alternative sources of energy, augmented by additional investment in oil and gas to ensure the security of the transition.

- We expect that there will be a number of opportunities associated with this transition, in particular in relation to the building, transport and industrial sectors.

An energy crisis

The current European energy crisis has arguably been years in the making. In 1990 the European Union (EU) imported approximately 50% of its natural gas demand; fast forward to 2021, and Europe imports close to 85% of its gas demand, with Russia having become the supplier of approximately 40% of total EU gas.1,2

Russia recently caught Europe off guard and ill-prepared with low gas inventories. Events over the last couple of years have provided the perfect storm to create a very tight European gas market. An acutely cold 2020/21 winter across multiple regions and lack of wind for wind-power generation took EU gas reserves down to half those of the previous year, at only around 30 bcm (billion cubic meters) versus EU storage capacity of 113.7 bcm.3 Storage inventories were then insufficiently replenished, with Russia blaming technical outages and plant fires for not delivering gas; however, the true reason became apparent with the invasion of Ukraine.

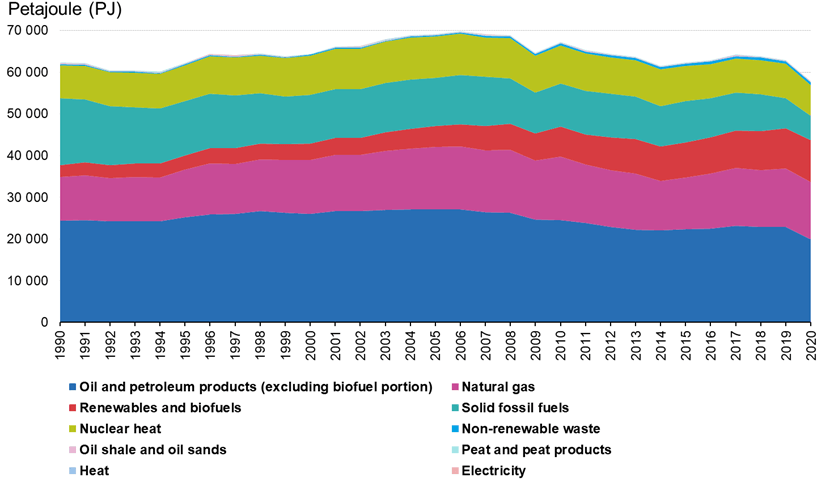

EU data from 2020 shows that 68% of total energy supply (not to be confused with electrical power generation) in the EU was produced from coal, crude oil and natural gas, with renewables accounting for only 17% of total energy supply.4 The growth in renewable energy power generation has largely been offset by the reduction in nuclear power generation. The current energy mix means that the EU is dependent on imports for 57.5% of its energy requirements, which clearly leaves it vulnerable to external shocks.5

Gross available energy by fuel, EU, 1990-2020

Source: Eurostat, February 2022

Ironically, European energy policy has partly been to blame for the fragility that is now emerging in energy systems. Last year, the EU announced a target to increase the share of renewable energy to 40% of final consumption by 20306 (up from 22.1% in 2020),7 and as countries have sought to decarbonise, the continent has become more dependent on Russian gas.

Energy transition

As a result, governments and policymakers are currently doing all they can to ‘keep the lights on’ – whether that is done by burning more coal, extending the life of nuclear power plants, or securing more oil supplies. This begs the question: have efforts to support the energy transition been thrown out of the window? In the short term, as the West continues to cut off Russia and reduce its reliance on Russian energy, the lifespan of fossil fuels is likely to be extended in order to meet economic needs. Nations are now scrambling to meet their energy needs, regardless of the source.

What this crisis has highlighted, however, is the need for countries to increase their clean-energy efforts – not only owing to the climate imperative, but also because of the close links to national security. The invasion of Ukraine and resulting sanctions have highlighted the geopolitical risks associated with the import and export of energy. Therefore, although the energy crisis may have negative effects on the environment in the short term, we believe that it is likely to accelerate the transition towards alternative energy sources in the medium and long term.

Climate policy

Despite this crisis forcing an increase in the use of fossil fuels, the European Parliament has voted overwhelmingly to maintain the rate at which the number of permits issued in the emissions trading scheme (ETS) decline; in other words, the scheme will continue to tighten and put pressure on industries to decarbonise. It is for this reason, we believe, that the ETS price of carbon has held reasonably firm despite the challenging economic and geopolitical backdrop.

In addition, the EU has proposed the REPowerEU package, consisting of almost €300bn to improve efficiency of fuels and a faster rollout of renewable power, to help EU countries move away from Russian oil, gas and coal.8 The European Commission has been seeking to set more ambitious goals since last year, and this new package of measures suggests that the current energy crisis is not weakening the momentum of climate policy in the EU.

Short-term implications

In the short term, we believe that power generation from sources other than gas in Europe will stand to benefit from the cut-off of Russian gas. Operators of power generation that are not subject to fuel supply from global markets, such as domestic coal or nuclear energy, could provide short-term relief from gas shortages. However, although non-gas power producers are theoretically well-positioned, they may face additional taxes or have caps imposed on the price at which they can sell electricity in order to combat the rise in consumer bills. Use of coal and (to an extent) biofuels is not aligned with the climate-change ambitions of the EU, but in the very short term this is likely to be overlooked out of necessity. Nuclear power is always controversial, though we think that it would be imprudent to decommission nuclear before a fully decarbonised grid has been built out. Therefore, we expect that nuclear facilities are likely to remain in operation for quite some time to come.

We believe that there is also an opportunity in liquefied natural gas (LNG) storage, transportation and production as the EU looks to build extra resilience into the existing energy system. Nevertheless, there should be one eye on the exit strategy, to make sure we are not locked into more decades of burning carbon.

Medium-term opportunities

It is clear that efforts need to be made to strive for a largely fossil-fuel-free energy system, necessitated not just by climate change, but also by energy security.

Power generation is, in principle, the simplest sector to decarbonise, given established technologies in wind and solar. We believe that investment opportunities will emerge across the supply chain, from developers of renewables to manufacturers of components used in renewables. A grid based on intermittent power is going to require significant upgrades, combining energy storage in the form of batteries and hydrogen with ultra-high-voltage cross-continental interconnectors.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the buildings and building construction sectors combined are responsible for almost one-third of total global final energy consumption,9 and we believe this is addressable in two ways. One is to accelerate the renovation and insulation of the current building stock and increase energy efficiency requirements for new buildings. The second is to speed up the rollout of heat pumps to replace gas and oil boilers. The introduction of heat pumps needs to go in tandem with improvements in building insulation in order to work effectively. Smart home control systems can also save a surprising amount of energy. At an EU level, reducing building heating by just 1°C can save 10 bcm of gas per year,10 out of a total 450 bcm gas demand.11

Transportation accounts for 37% of CO2 emissions from end‐use sectors, according to the IEA.12 This sector presents a mixed picture; light vehicle transport is easily replaced with battery electric vehicles, the technology for which has already been proven. We are seeing investment opportunities in the electric-vehicle supply chain and charging infrastructure. On the other hand, heavy road transport, shipping and aviation are much more expensive to decarbonise. This area is likely to start to see investment, but may not be the main area of focus in the near term.

The manufacturing industry, by nature of its focus on producing products at the lowest possible cost, is already fairly efficient; however, the current high electricity prices make the payback period for installing more energy-efficient components like compressors much shorter, and therefore may accelerate investment. Heavy industry requiring high heat intensity to produce goods is likely to require a shift to hydrogen as a fuel source, which requires significant investment in technology and infrastructure. We believe that there may be opportunities in industrial gas, manufacturing of electrolysers, and speciality chemical companies developing cathode materials.

Energy security and net zero

As the current European energy crisis persists, although the short-term implication may be a setback to the energy transition, we believe that over the medium and long term it could in fact accelerate the shift to alternative energy sources. The links between increasing European energy security and achieving net-zero climate-change ambitions are striking, which gives us confidence that energy security and decarbonisation are not mutually exclusive.

Sources:

- Eurostat, Energy statistics – an overview, February 2022

- Reuters, Factbox: How can Europe get gas if Russia’s supply is disrupted?, 11 May 2022

- European Parliamentary Research Service, EU gas storage and LNG capacity as responses to the war in Ukraine, April 2022

- Eurostat, Energy statistics – an overview, February 2022

- Ibid.

- Reuters, EU unveils plan to increase renewables share in energy mix to 40% by 2030, 14 July 2021

- Eurostat, Renewable energy statistics, January 2022

- EUR-Lex, REPowerEU Plan, 18 May 2022

- IEA, Buildings, accessed 1 August 2022: www.iea.org/topics/buildings

- IEA, 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union’s Reliance on Russian Natural Gas, March 2022

- Statista, Natural gas consumption in the European Union from 1998 to 2021, 19 July 2022

- IEA, Transport, accessed 1 August 2022: https://www.iea.org/topics/transport

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Newton manages a variety of investment strategies. Whether and how ESG considerations are assessed or integrated into Newton’s strategies depends on the asset classes and/or the particular strategy involved, as well as the research and investment approach of each Newton firm. ESG may not be considered for each individual investment and, where ESG is considered, other attributes of an investment may outweigh ESG considerations when making investment decisions.

Important information

This material is for Australian wholesale clients only and is not intended for distribution to, nor should it be relied upon by, retail clients. This information has not been prepared to take into account the investment objectives, financial objectives or particular needs of any particular person. Before making an investment decision you should carefully consider, with or without the assistance of a financial adviser, whether such an investment strategy is appropriate in light of your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances.

Newton Investment Management Limited is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence in respect of the financial services it provides to wholesale clients in Australia and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the UK under UK laws, which differ from Australian laws.

Newton Investment Management Limited (Newton) is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN. Newton is providing financial services to wholesale clients in Australia in reliance on ASIC Corporations (Repeal and Transitional) Instrument 2016/396, a copy of which is on the website of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, www.asic.gov.au. The instrument exempts entities that are authorised and regulated in the UK by the FCA, such as Newton, from the need to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act 2001 for certain financial services provided to Australian wholesale clients on certain conditions. Financial services provided by Newton are regulated by the FCA under the laws and regulatory requirements of the United Kingdom, which are different to the laws applying in Australia.

Comments