We assess the possible investment and geopolitical implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Key points

- Russia’s position as a commodity powerhouse, coupled with high commodity prices, is likely to be what emboldened President Putin to take the revisionist steps he has done over Ukraine.

- We expect accelerated defence spending within European budgets, and for this to be an important area of growth in future years, following Russia’s Ukraine invasion.

- We think that completely alienating Russia from the Western economic system is not a viable path, as this would create immense self-harm for Western economies.

- The medium-term implication of dependence on Russian commodities will be a concerted effort by Europe to diversify to other suppliers, and also to boost investment in renewable sources of energy.

- We anticipate that Russia and China will double down on their efforts to cooperate in trade and technology.

Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 has shocked financial markets. As is often the case with geopolitical events, we believe that this event itself is likely to signify peak fear for investors, so there should be opportunities to tactically add to risk assets. However, given the profound geopolitical significance of this particular event – the first time a great power has invaded a fully independent sovereign state since World War II – we also believe it has more fundamental medium and long-term implications for economies and markets than most ‘typical’ geopolitical events. This should present both opportunities and risks for investors, and below we set out what we believe are the main implications investors need to consider.

Sanctions

To fully appreciate the new landscape post Ukraine invasion, investors need to understand the nature of Western sanctions that have been imposed on Russia. A wave of sanctions had already been imposed earlier this week following Russia’s recognition of the separatist republics in Donetsk and Luhansk. These included trading bans on Russian sovereign debt, the sanctioning of two Russian state banks, individual sanctions on specific oligarchs and members of Russia’s Duma, and the certification suspension of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. They were all targeted measures but generally non-systemic in the economic pain they would be likely to cause for Russia.

By contrast, the latest wave of sanctions announced in the last 24 hours (25 February) in response to Russia’s Ukraine invasion are far broader and more systemic, and will have a significant impact both on Russia’s economy and Russia’s integration with the West. They encompass export restrictions on semiconductors, software and other technologies that target Russia’s defence, aerospace and life-sciences industries, plus sanctions across 80% of Russia’s banking system, including the financial behemoth Sberbank. Importantly for Western economies (and a potential lifeline for Russia’s), payments for energy purchases will be carved out of the sanctions. Lastly, the US is still considering the eventual possibility of expelling Russia from the SWIFT international payment system but has not done so in these latest measures.

Investment implications

1. Commodities: inflation, disruption, larger Western investment

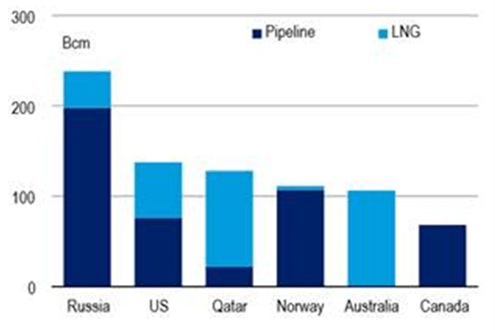

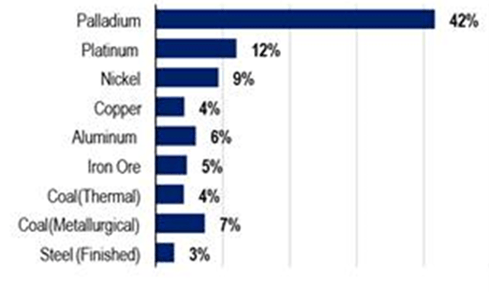

Russia’s position as a commodity powerhouse, coupled with high commodity prices, is likely to be what emboldened Putin to take the revisionist steps he has done over Ukraine. Russia is the largest natural-gas exporter in the world, exporting equivalent volumes to the number two and three players combined. Significantly, Russia supplies 40% of Europe’s gas, a share that has been growing in recent years as domestic sources have matured. In oil markets, Russia is the second-largest producer and exporter after Saudi Arabia. In metals, the country has an approximately 5% global production market share in most categories, but this is significantly higher for precious metals including the PGMs (platinum-group metals) that are strategically important for emissions reduction and managing climate change.

Lastly, in soft commodities, Russia and Ukraine have been notable success stories since the end of the Cold War in raising farm yields and productivity. While the Soviet Union was a periodic importer of grains, Russia and Ukraine now account for 25% of world grain exports, so hold considerable control over food markets. These statistics serve to indicate Russia’s importance to the global economy, to supply chains and to inflation at this particularly sensitive time. Therefore, completely alienating Russia from the Western economic system is not a viable path, as this would create immense self-harm for Western economies.

Russia’s gas export dominance

Russia’s global share of metals production

Source: Bank of America Global Research, 2020

While we expect that commodity trade will continue between Russia and the West, the continuing geopolitical tensions and confrontational relations will make for a bumpy journey and periods of heightened volatility. For example, there have already been reports of Western banks refusing to grant letters of credit to purchasers of Russian oil owing to sanctions. Commodity markets, by their fungible nature, normally clear, but we see scope for commodities trade between Russia and the West to become more indirect, inevitably creating opportunities for traders, but also raising costs for the end user. Furthermore, investors cannot rule out periods of supply disruption as Russia becomes a less dependable partner, with a particular risk for natural gas given Europe’s high energy dependency.

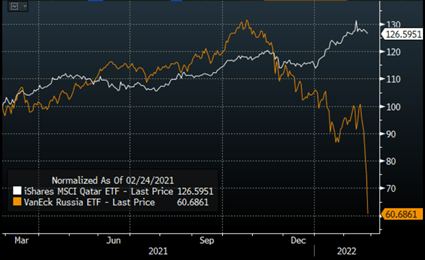

The medium-term implication of Russian commodity dependence will be a concerted effort by Europe to diversify to other suppliers. In the natural-gas space this would include Qatar, Australia and the US, which are all likely to see accelerated investment in their liquefied natural gas (LNG) capacities. Qatar, for example, has already been in close discussions with the West throughout the recent Ukraine tensions regarding emergency gas supplies. In the medium term, Qatar plans to increase its LNG production from 77 million tonnes per year (mtpa) today to 126 mtpa by 2027, and a sizeable portion of this incremental growth will find its way to European markets. The second implication is likely to be an even more accelerated path towards renewable energies as these are seen as an important basis for national security in addition to the green agenda. We expect the nuclear, hydrogen, wind and solar industries to take on added importance in the wake of the Ukraine geopolitical event.

Beneficiaries of the conflict

Qatar vs Russia 12-month equity-market performance (as captured by exchange-traded fund pricing)

Source: Bloomberg, 24 February, 2022

2. Western security: After Ukraine, what and where next?

Throughout history, emboldened great powers have typically proceeded to seek greater territorial expansion. Putin has a personal mission to right the perceived inequities of the Soviet Union’s dissolution. The Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, with notable ethnic Russian populations, were once part of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. They became NATO members in 2004 and all three have since become members of the eurozone. With Russia firmly in control of Ukraine, the bordering European Union (EU) countries including Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and Romania, as well as the Baltic states mentioned above, will face greater risk of political, economic and social destabilisation, and investors should expect a higher sovereign-risk premium to compensate them for investing in these countries.

Putin has stated that Russia has no intention of occupying Ukraine. However, he also repeatedly stated that Russia had no intention of invading Ukraine, and that the West was suffering from paranoia and hysteria. Yesterday’s actions serve to highlight the deep lack of credibility and heightened distrust that European countries will have towards Russia in the future.

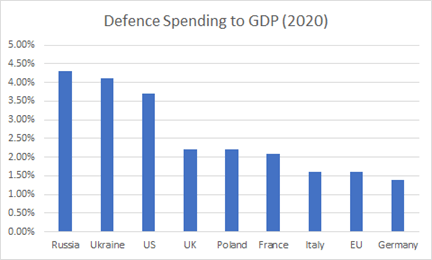

This distrust will evolve in the shape of a new Cold War, or ‘Cold War 2.0’ as we have previously written about, and will necessitate a sharp increase in defence spending, particularly by European countries given the proximity of Ukraine and, in Churchill’s words, a new ‘iron curtain’ that will be likely to descend over Europe. The domestic divisions that the United States is facing at home mean that European countries cannot afford to, and should not, remain overly dependent on the US security blanket over the medium term.

Most European countries have increased defence spending in recent years, but several countries – most notably Germany – remain well below the 2% of GDP NATO target. We expect accelerated defence spending will be an important feature of European budgets, and an important area of growth for the market in future years, following Russia’s Ukraine invasion.

While a large portion of national-defence spending would be state-led in critical areas of contestation such as space, hypersonic weapons and drones (and should benefit the European and US defence primes), there will be an ever-growing portion of private-sector defence spending as companies allocate a growing share of spending to the protection of their critical infrastructure and IT systems. The growth outlook for the cyber-security industry looks strong in any case, but even stronger with a hostile and alienated Russia.

US, European and Russian defence spending as % of GDP

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Newton, 2021

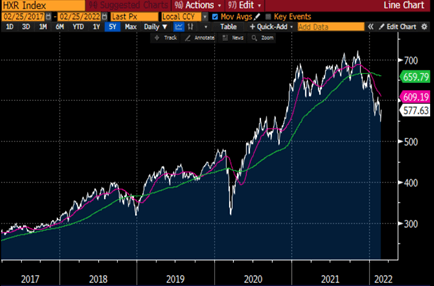

ISE Cyber Security Index: Positive tailwinds

Source: Bloomberg, 25 February, 2022

3. Inflation and central-bank policy – the dreaded ‘s’-word

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has been carefully and tactically orchestrated not only to coincide with Europe’s seasonally high demand for Russian gas, but also to coincide with a period of high commodity prices, excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus and supply-chain disruptions, which have fed through to the highest consumer-price inflation in almost 40 years. The invasion of Ukraine and political after-effects will almost certainly add further proverbial fuel to the inflationary fire.

We believe the underlying supply-demand fundamentals of the energy market would put Brent crude oil at around $85 a barrel, so the current $101 oil price (on 25 February) implies a geopolitical-risk premium (to compensate for possible disruption) of around $15 per barrel of oil. This is not an unusually high level of premium compared with previous geopolitical risk events, and we expect that the premium could persist for a lot longer than has been the case with many other events as the confrontation with, and alienation of, Russia will endure.

This dynamic presents a natural headache for central-bank policymakers. Just as the US Federal Reserve is expected to make its first rate hike in mid-March, and the European Central Bank (ECB) seeks to wind down quantitative easing and follow with a rate hike of its own later in the year, the spectre of stagflation now confronts the monetary-policy establishment.

Higher inflation prospects would naturally prompt central banks to tighten policy, but at the same time – particularly for the European economy – the Ukraine invasion and prospect of energy-supply disruptions will have a dampening effect on business and consumer confidence. Economic data over the coming months will need to be watched closely to determine whether geopolitics is affecting economic sentiment. As things stand, we fully expect the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to press on with its first and subsequent rate hikes in the first half of 2022, but remain to be convinced that the Fed will execute on the full seven rate hikes implied by money markets – particularly given the sharp flattening of the yield curve that has occurred in recent months. For the ECB, withdrawing liquidity from markets is likely to have an outsized impact on corporate credit spreads given its €40bn of buying activity in credit during the global pandemic. Therefore, the ECB could find itself with the uneasy prospect of having to sell corporate bonds back to the market just as Russia-Ukraine uncertainty is beginning to feed into European corporate credit malaise.

We would expect the threat of further sanctions and heightened tensions to keep energy prices high, but unless there is a material interruption to the energy supply the economic hit (thereby causing stagflation) could be less. This, in turn, will allow the central banks to start their tightening cycle, but may reduce the terminal rate.

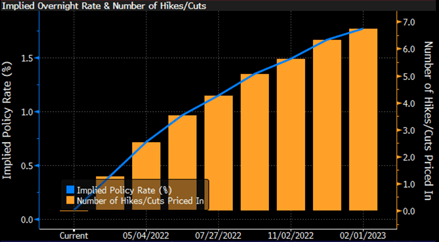

US Federal Reserve implied rate hikes in 2022

Source: Bloomberg, 25 February, 2022

US sovereign yield curve (10yr-2yr) rapidly flattening

Source: Bloomberg, 25 February, 2022

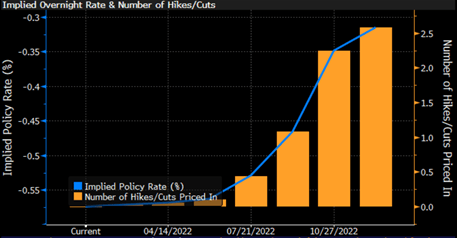

ECB implied rate hikes for 2022

Source: Bloomberg, 25 February, 2022

ECB corporate bond purchases in 2020-2021

Source: Bloomberg, 25 February, 2022

4. Sino-Russian cooperation – still a relationship of convenience, but getting closer

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the US announced tough export restrictions on critical technology applications to Russia, including software and semiconductors. The EU has also said it will put export restrictions on industrial technologies that are valuable for Russia’s growth. Although technology sanctions will cause deficiencies for Russia in certain areas such as defence technology, the country’s lack of dependence on high-end manufacturing will be likely to prevent significant disruption. One effect will be to see Russia and China double down on their efforts to cooperate in trade and technology. Both countries already have a strategy to increase bilateral trade from a level of $140bn in 2021 to $200bn in the medium term.

The long-term Sino-Russian cooperation strategy was in clear evidence in Putin’s statement to President Xi and the Chinese people that accompanied his recent visit to the Beijing Winter Olympics. Putin referred to 65 bilateral investment projects currently in the pipeline worth a prospective investment sum of $120bn. Already, within the technology sphere, Russia provides civil nuclear assistance to China, but the speech listed a wider range of areas where technological cooperation and partnerships can be expanded, including in IT, medicine and space exploration, the latter being an area with significant scope for civilian technology spin-offs.

Despite closer Sino-Russian cooperation expected in the coming years, the asymmetric economic balance of power between the two countries, with China’s GDP some nine times larger than Russia’s in nominal terms, means that Moscow won’t want to become overly dependent on Beijing. Memories of Cold War enmity between China and the Soviet Union and caution over spheres of influence in Central Asia will be ever present. We do not anticipate an official mutual defence pact between Russia and China to be a likely prospect. Instead, the Sino-Russian relationship will be one of economic and diplomatic convenience.

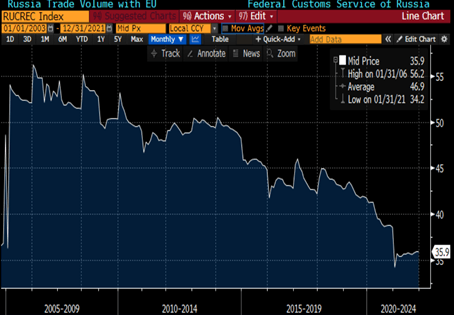

Russia trade volume with EU (% total trade)

Source: Bloomberg, February 2022

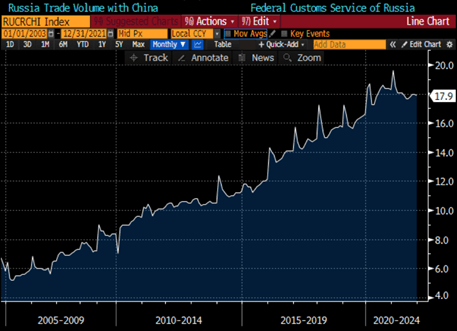

Russia trade volume with China (% total trade)

Source: Bloomberg, February 2022

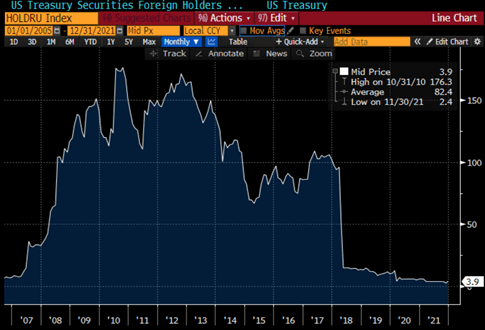

Given the latest sanctions, Russia will become practically isolated from the Western financial system, save for payments to purchase its commodities. As the Russian state and Russian companies become increasingly self-funded but unable to import from the West, the country will have few demands for US dollars. In anticipation of Western financial decoupling, since 2018 Russia’s central bank has already reduced its US Treasury holdings to close to zero.

Russia’s foreign reserves decoupled from foreign debt

Source: Bloomberg, February 2022

Russia has sold almost all its US Treasury holdings

Source: Bloomberg, February 2022

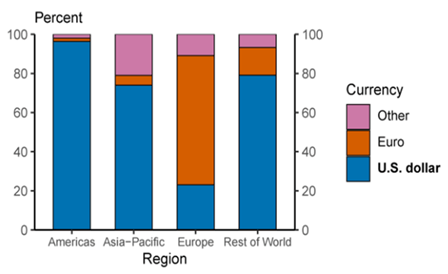

President Putin’s recent Beijing Winter Olympics statement highlighted a growing propensity for Sino-Russian trade to take place in local currencies, highlighting that the two countries “are consistently expanding settlements in national currencies and creating mechanisms to offset the negative impact of unilateral sanctions”. Meanwhile Chinese officials are also pushing for greater local-currency usage as they support economic development across the Indo-Pacific region. By economically and financially alienating Russia and pushing the country into a closer embrace with China, the contours of a new global currency regime are perhaps beginning to take shape. The US dollar will retain its primacy for some time yet, but this dominance is coming into question and being eroded at the margin, with Russia’s exclusion from the dollar-based system the latest development in this long-term trend. At the same time, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is elevating itself as a paragon of monetary discipline: real rates are positive, Chinese consumer-price inflation is benign (0.9% year on year in January), and there is a strong reluctance to slash rates to restart an aggressive credit cycle. Global investors need to take account of the evolving position of the US dollar and other currencies as they perform their continuing asset allocation in a world in which Russia and China are more closely economically aligned.

US dollar share of global reserves – a 25-year low

Source: US Federal Reserve, 6 October 2021

Share of export invoicing – Asia-Pacific to follow Europe?

Source: US Federal Reserve, 6 October 2021

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility, owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices. Richard Bullock is an employee of BNY Mellon Investment Management Singapore and provides support to Newton Investment Management as a geopolitical strategist.

Important information

This material is for Australian wholesale clients only and is not intended for distribution to, nor should it be relied upon by, retail clients. This information has not been prepared to take into account the investment objectives, financial objectives or particular needs of any particular person. Before making an investment decision you should carefully consider, with or without the assistance of a financial adviser, whether such an investment strategy is appropriate in light of your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances.

Newton Investment Management Limited is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence in respect of the financial services it provides to wholesale clients in Australia and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the UK under UK laws, which differ from Australian laws.

Newton Investment Management Limited (Newton) is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN. Newton is providing financial services to wholesale clients in Australia in reliance on ASIC Corporations (Repeal and Transitional) Instrument 2016/396, a copy of which is on the website of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, www.asic.gov.au. The instrument exempts entities that are authorised and regulated in the UK by the FCA, such as Newton, from the need to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act 2001 for certain financial services provided to Australian wholesale clients on certain conditions. Financial services provided by Newton are regulated by the FCA under the laws and regulatory requirements of the United Kingdom, which are different to the laws applying in Australia.

Comments