The music industry has returned to growth thanks to the rise of streaming. Can the momentum be maintained?

Key points

- The adoption of music streaming is still in its early stages, with the prospect of many years of secular growth ahead.

- The cost of recorded music for consumers has fallen significantly in real terms over the last two decades, which should enable streaming providers to pass on price rises in the coming years.

- Streaming has transformed the economics of the music industry, with older, catalogue music earning a greater proportion of total revenues, and a larger share of the revenue pool accruing to rights holders.

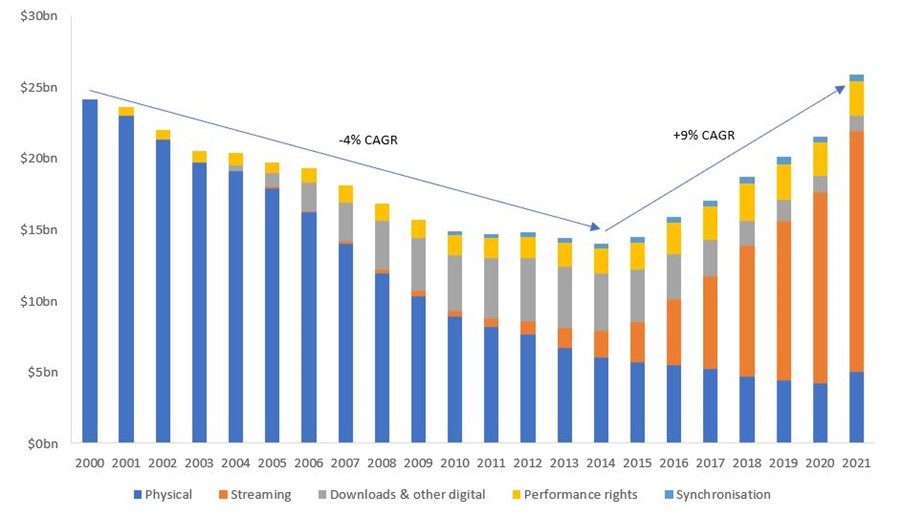

For more than a decade following the turn of the millennium, revenues for the recorded music industry had been on a steady decline due to the rise of online piracy, as well as the unbundling of music albums made possible by services such as iTunes. Between 2001 and 2014, revenues for the global recorded music industry fell by 42%, equivalent to 4% per year.

However, the rapid growth of online streaming services such as Spotify led to an inflection point in industry revenues in 2015, as a greater share of the population was once again paying for the music it consumed. Since 2014, industry revenues have risen by 85%, or 9% per year.

Global recorded music industry revenue, 2000-2021

Source: IFPI, March 2022. CAGR = compound annual growth rate.

With streaming services now accounting for two thirds of industry revenues, and growing at 26% in 2021, the music industry is now exhibiting strong secular growth.

Subscriber growth to remain strong

Although we have now seen several years of high growth in industry revenues thanks to the rise of streaming, adoption still appears to be in its early stages. Total streaming penetration amounted to just 8% of the global population in 2021, well below the 45% seen in Sweden, Spotify’s home market. Even in mature markets, there remains ample room for the number of streaming subscribers to rise. In the US, for example, streaming penetration is still only 38%.[1] We expect revenues for the recorded music industry to double over the next ten years thanks to continued strong subscriber growth.

Potential drivers of subscription growth over the coming years include the improved user experience and increasing connectivity, leading to both increased consumption and willingness to pay. The average person globally now spends over 18 hours each week listening to music.[2]

Is this level of growth really sustainable?

While such high-revenue growth might seem unsustainable at first sight, it is important to bear in mind that this is in the context of industry revenues which had been declining for 15 years. Last year, industry revenues finally recovered to levels seen in 1999 in nominal terms, yet they remain well below this level once inflation is accounted for. After adjusting for the inflation rate, we estimate that industry revenues are still 38% below the previous peak. [3] This implies that the cost of recorded music for consumers has fallen significantly in real terms over the last two decades, which should enable streaming providers to pass on price rises in the coming years.

Comparing music industry revenues to other forms of content such as the audiovisual market presents an even starker picture. For example, the revenues of the global audio-visual market increased almost five-fold between 2000 and 2020,[4] compared to music industry revenues which were largely flat. This illustrates the extent to which music industry revenues have been depressed by the rise of online piracy and the unbundling of albums through digital downloads, while consumers’ willingness to pay for entertainment has significantly increased over this period. The shift towards a streaming model leaves the industry well positioned to capture a greater share of the value it provides to consumers.

The industry has significant latent pricing power

Given that the real cost of music has fallen significantly for consumers over the last two decades and their willingness to pay for a streaming subscription is likely to be far higher than the current cost, we would expect material price rises to occur over the long term once streaming adoption has matured. Per-capita spending on music in the US is currently less than half of what it was in 1999,[5] and over 70% below in real terms.

In the audio-visual market, we are already starting to see some price rises filter through in the US and Europe; the price of a Netflix subscription, for example, has risen by 5-8% annually since 2014. Conversely, the average price of a standard music streaming subscription has remained unchanged for the last decade.

The new paradigm of the music industry

The shift from a one-off outright sales model to a recurring subscription-based model has fundamentally transformed the economics of the music industry. In a streaming world, revenues are shared based on listening. This means that older, catalogue music which users continuously listen to earns a greater proportion of industry revenues. This increases the visibility of revenues and reduces the industry’s reliance on new hits, which can be volatile.

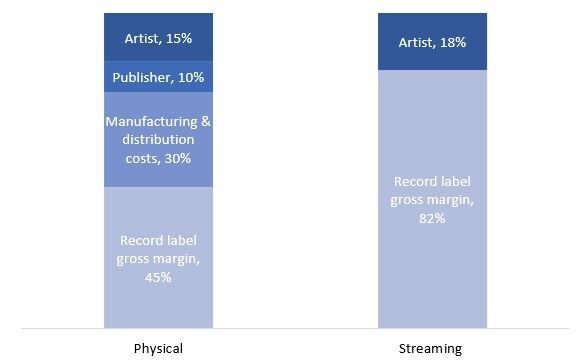

Not only does streaming improve the visibility and growth in industry revenues, but a greater share of this revenue pool is attributable to rights holders, including record labels, artists and songwriters. This is a result of the elimination of manufacturing and distribution costs for physical media such as compact discs, as well as lower marketing costs as established, catalogue music becomes more important.

Share of revenues – physical vs. streaming music

Source: J.P. Morgan research, March 2019.

In summary, the shift to a subscription-based streaming model has revitalised the growth trajectory of the music industry. We expect another decade of visible high-single-digit revenue growth, alongside a greater share of the economics accruing to the rights holders of valuable catalogue music. We believe this provides a compelling opportunity for long-term thematic investors.

[1] Source: Company reports, August 2021.

[2] Source: IFPI, October 2021.

[3] Source: IFPI, company reports, World Bank, Newton estimates, August 2021.

[4] Source: J.P. Morgan estimates, July 2021.

[5] Source: Company reports, World Bank, Newton estimates, August 2021.

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Important information

This material is for Australian wholesale clients only and is not intended for distribution to, nor should it be relied upon by, retail clients. This information has not been prepared to take into account the investment objectives, financial objectives or particular needs of any particular person. Before making an investment decision you should carefully consider, with or without the assistance of a financial adviser, whether such an investment strategy is appropriate in light of your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances.

Newton Investment Management Limited is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence in respect of the financial services it provides to wholesale clients in Australia and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the UK under UK laws, which differ from Australian laws.

Newton Investment Management Limited (Newton) is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN. Newton is providing financial services to wholesale clients in Australia in reliance on ASIC Corporations (Repeal and Transitional) Instrument 2016/396, a copy of which is on the website of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, www.asic.gov.au. The instrument exempts entities that are authorised and regulated in the UK by the FCA, such as Newton, from the need to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act 2001 for certain financial services provided to Australian wholesale clients on certain conditions. Financial services provided by Newton are regulated by the FCA under the laws and regulatory requirements of the United Kingdom, which are different to the laws applying in Australia.

Comments