We explore the investment implications and financial materiality of biodiversity.

Key points

- Given the intangible and complex nature of the topic, applying a biodiversity lens to investment decisions is not straightforward.

- We believe that any biodiversity investment framework needs to be designed to evolve as our scientific understanding, regulation and industry-leading practices develop.

- There are numerous ways in which biodiversity can have an impact on a business and investments, and these financially material risks can be physical, transitional or systemic in nature.

- We expect such risks to emerge more frequently in the future, as we have seen with climate change.

Application to investments

Taking a topic as intangible and complex as biodiversity and applying it to investment decisions is not easy. There are lessons that can be learnt from how the investment industry has approached climate change, but biodiversity has its own additional challenges. A tonne of carbon emitted anywhere on the planet has very similar real-world outcomes, whereas one particular tree lost or planted in a region does not have the same impact as the same tree in another location, or indeed a different species in the same location. The role of location-based data and the need for granularity is especially important in relation to biodiversity, even relative to other environmental issues.

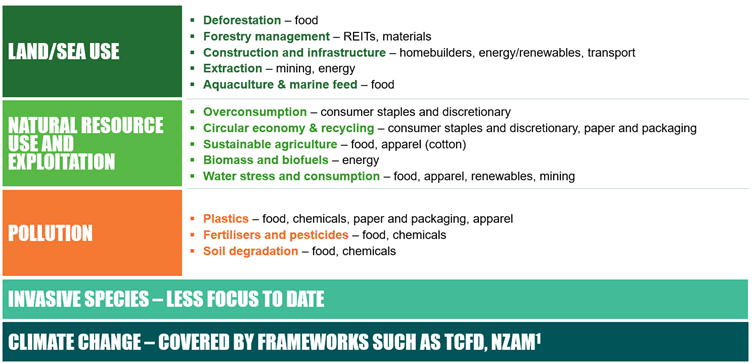

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is a leading authority on the science of biodiversity and public policy responses. It cites five direct drivers of biodiversity loss: (1) land and sea use and change, (2) natural resource use and exploitation, (3) pollution, (4) invasive species, and (5) climate change. These can be viewed as a channel through which humans have an impact on nature, and as we begin to build out our own framework, we are looking at using these to connect biodiversity to investments.

The five drivers can first be connected to corporate activities, and subsequently industries that we may invest in. This is essentially a materiality mapping exercise – one in which we can take tangible components of one issue and consider how different industries may affect it. Below is an indicative example of how each driver links to specific issues and industries (it is not exhaustive). We find that the connection of our scientific understanding of what is driving biodiversity loss to the products and services that companies offer, and the way in which they produce or conduct these, is one of the key areas for investors to bridge.

Financials play an overarching role

Note: 1 TCFD = Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures; NZAM = Net Zero Asset Managers initiative.

The issues highlighted above are not new environmental challenges – deforestation, plastic pollution and water stress are all well understood by investors and companies. In some ways, biodiversity is now used as a new lens through which to view these issues, and we are even seeing some use the term to refer to any environmental issue that is not explicitly climate change, which highlights the breadth of this topic. This means that many of the biodiversity targets and engagements we now see discussed are not necessarily new but are the relabelling of existing initiatives. As investors, we need to be aware of this, but equally, the nature of the subject means that it requires breaking down into actionable issues. Work has already been done on some of these, but the focus on biodiversity enables us to concentrate more on the real-world impacts of these, and at a systems level, rather than in isolation.

At present, this still has its limitations. We believe that any biodiversity investment framework needs to be designed to evolve as our scientific understanding, regulation and industry-leading practices develop. For example, there is currently very little research on invasive species and the way in which corporate activities may affect them. The problem regarding the grey and red squirrels is well known – the introduction of the American grey squirrel has led to the endangerment of the European and Asian red, as the greys carry a specific virus that can kill the red squirrels, and they also eat the red’s primary food source before they are able to consume it. However, it is not easy to identify and analyse the way in which corporate activities influence such practices.

Financial materiality

There are numerous ways in which biodiversity can have a financial impact on a business and investments. We have seen limited examples to date but expect such risks to emerge more frequently in the future, as we have seen with climate change. Often, the ESG (environmental, social and governance) case studies that we see demonstrating financial materiality are those where a risk materialises from a significant catalyst – a strike resulting in cancelled flights, labour issues in a supply chain being investigated by governments or NGOs (non-governmental organisations), or physical risks destroying land or property. We have not yet seen this type of acute risk within biodiversity – it may indeed be more chronic in nature. Moreover, given that this is such an intangible topic, and one often used as an umbrella term for a range of specific concerns, such as deforestation, we may not see events labelled as biodiversity issues, where in fact they are. Water stress affecting operations and supply chains is a good example of this.

In terms of how biodiversity issues can have a financially material impact on a company, first there are physical risks. For instance, biodiversity loss is linked to deforestation, which exacerbates climate change by reducing the planet’s carbon sequestration abilities, as well as its ability to provide humans with protection against extreme weather events. Biodiversity is also interconnected with soil degradation, which negatively affects agricultural yields and therefore our ability to produce foods efficiently. Furthermore, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations notes that pollinators affect 35% of global land use for agriculture, which covers the production of 87 of the leading global food crops.1

In May 2020, the European Union adopted a Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, which aims to protect nature and restore ecosystems. This will seek to increase the number of protected sites and will include binding nature restoration targets. It will also create funding to improve understanding of biodiversity, monitor impacts, and ensure these are integrated into business and investment decision making.2 Consequently, there are clearly transition risks as regulation and international coordinated efforts to promote biodiversity increase.

Finally, there are systemic risks as a result of human reliance on biodiversity. For example, approximately 60,000 plant species are harvested for traditional or modern medicine, comprising key raw materials in professional medicines and consumer products.3 It is likely that the medicinal benefits of many natural resources have yet to be discovered, as plants are often crucial to our understanding of medicines and biology, from peppermint as a natural antispasmodic to ginger as a treatment for nausea. Many ecosystems have been underexplored (e.g. the ocean) and new species of plants and animals are regularly being identified – suggesting that there are many species and therefore benefits yet to be discovered. Furthermore, research suggests that infectious diseases can thrive where biodiversity has been depleted. As the Dasgupta Review: The Economics of Biodiversity highlights, if nature is undisturbed, it will generate life, and continue to provide services that we do not pay for, but are of great benefit to humankind.

Sources:

- Why bees matter: The importance of bees and other pollinators for food and agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 20 May 2018

- Biodiversity strategy for 2030, European Commission

- CITES and Medicinal Plants, CITES, accessed 19 April 2023: https://cites.org/eng/prog/medplants

Your capital may be at risk. The value of investments and the income from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the original amount invested.

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This is not investment research or a research recommendation for regulatory purposes. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Newton manages a variety of investment strategies. Whether and how ESG considerations are assessed or integrated into Newton’s strategies depends on the asset classes and/or the particular strategy involved, as well as the research and investment approach of each Newton firm. ESG may not be considered for each individual investment and, where ESG is considered, other attributes of an investment may outweigh ESG considerations when making investment decisions.

Glossary

We provide a glossary of terms that you may find useful.