In many walks of life, identifying a problem is one thing, but solving it is quite another. This is certainly the case when we consider China’s attempts to adjust its economic and monetary trajectory after a sustained period in which the country’s rapid re-industrialisation went hand-in-hand with massive investment spending.

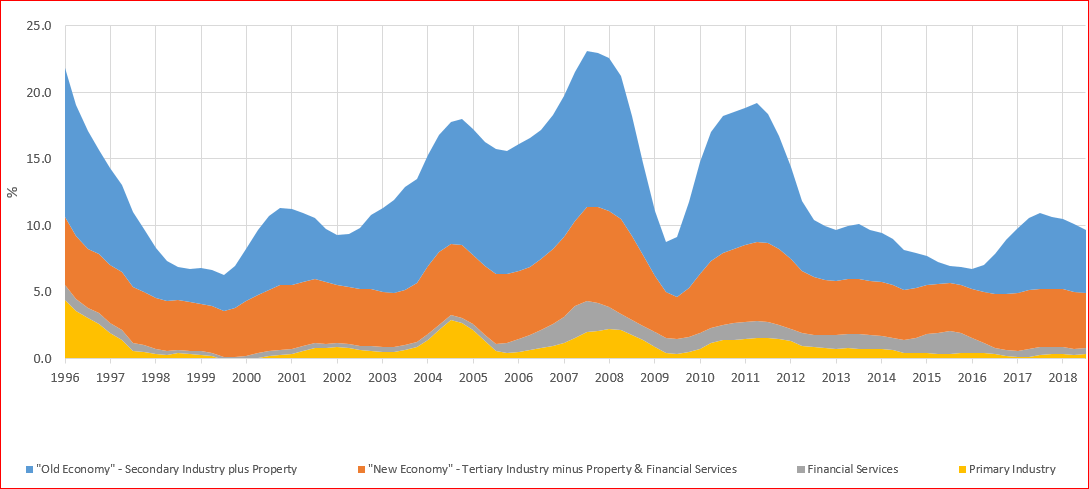

As a share of GDP, China’s investment spending reached unprecedented levels in the years leading up to and following the global financial crisis. This was, of course, unsustainable over the longer term, and it was widely recognised by China’s policymakers that the economy must be ‘rebalanced’, with domestic consumption needing to account for a larger share of output and overall investment needing to decline. This has been commonly depicted as a rebalancing away from the ‘old economy’ (secondary industries such as manufacturing and oil refining plus property) to the ‘new economy’ (service industries such as computer services and tourism). The chart below shows how China’s rapid economic growth prior to the global financial crisis was driven by the ‘old economy’.

Breakdown of contribution to China’s % year-on-year nominal GDP growth by industry

Source: Bloomberg 4/4/19

If China’s economy was to be rebalanced, it was inevitable that economic growth would slow, which the chart clearly shows to be the case, particularly since 2012.

However, what has not been discussed quite so frequently is the fact that, whenever policymakers have needed to stimulate the economy, it has tended to be the constituents of the ‘old economy’ which have been ‘juiced up’. The chart above also shows how the acceleration of the Chinese economy between 2009-11 and 2016-17 was almost entirely driven by the ‘old economy’. More than anything, within that, it is the property sector that drives the big swings in China’s economic growth. Property accounts for 86% of household wealth, while 87% of urban households own their own property and 27% own at least one empty investment property. Around 65% of loans are backed by property collateral, and the government funds 60% of its spending through land sales, which depend in turn on rising prices for empty investment properties.

Combined, the statistics point to the property market as the lynchpin of the Chinese economy. For all the talk of a consumer-led rebalancing, if Chinese monetary stimulus is going to help drive a reacceleration of global growth this year it won’t be via the Chinese consumer, but instead it will be through China’s property market.

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility, owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices.

Comments