In our view, there are two ways in which to define quantitative easing (QE); first, there is the volume of assets purchased, and, second, the impact that those security purchases have on broader money supply.

The two are not the same; only purchases of securities from a non-bank counterparty result in the creation of a new bank-deposit liability which directly boosts money supply. Everything else can be simply described as an asset swap between the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and a commercial bank.

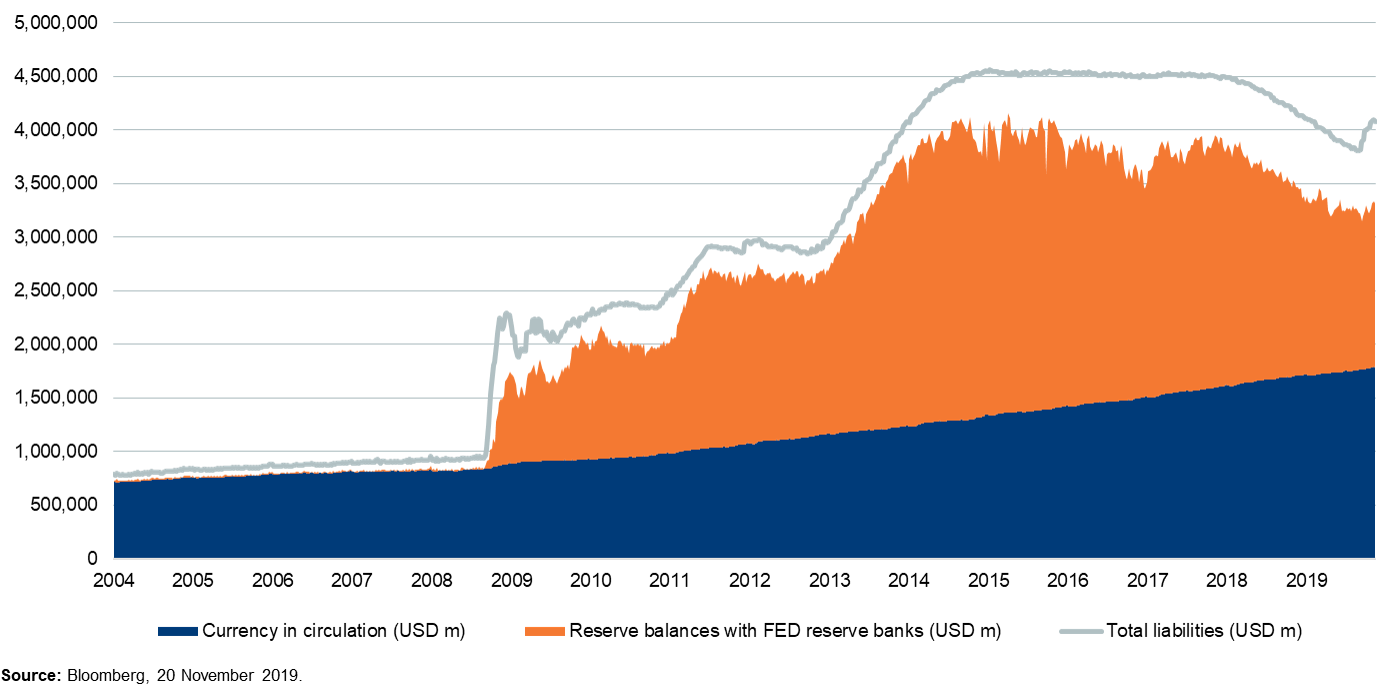

In the context of the second definition, although the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet (represented by the grey line in the chart below) is widely used for illustrative purposes, we believe it doesn’t tell the whole story. In our view, in order to assess QE properly, it is important to focus on the increase in commercial bank reserve balances with the Fed – as represented by the orange colour in the chart below.

What is clear to us from the chart is that the last 12 weeks of Fed balance sheet expansion (up to 20 November 2019) have not led to an increase in commercial banks’ reserve assets.

Federal Reserve balance sheet – currency and reserves

As commercial-bank reserves shrink, greater emphasis is placed on the commercial banks’ other high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to meet their regulatory requirements, in particular US Treasuries. Commercial banks’ reserves shrink naturally over time, as the Fed’s non-reserve liabilities (mainly currency) grow (represented by the blue series in the chart above).

However, commercial banks saw an accelerated decline in their excess reserves between mid-August and mid-September. As businesses paid their taxes, money balances were transferred from the commercial banks to the government, reducing the outstanding stock of commercial banks’ reserves and concurrently increasing the US Treasury General Account (TGA), the general checking account of the Department of the Treasury, by around $170bn.This reduced the stock of HQLA available to the commercial banks by an equal amount, which led to increased stress in the funding markets and increased demand for US Treasuries.

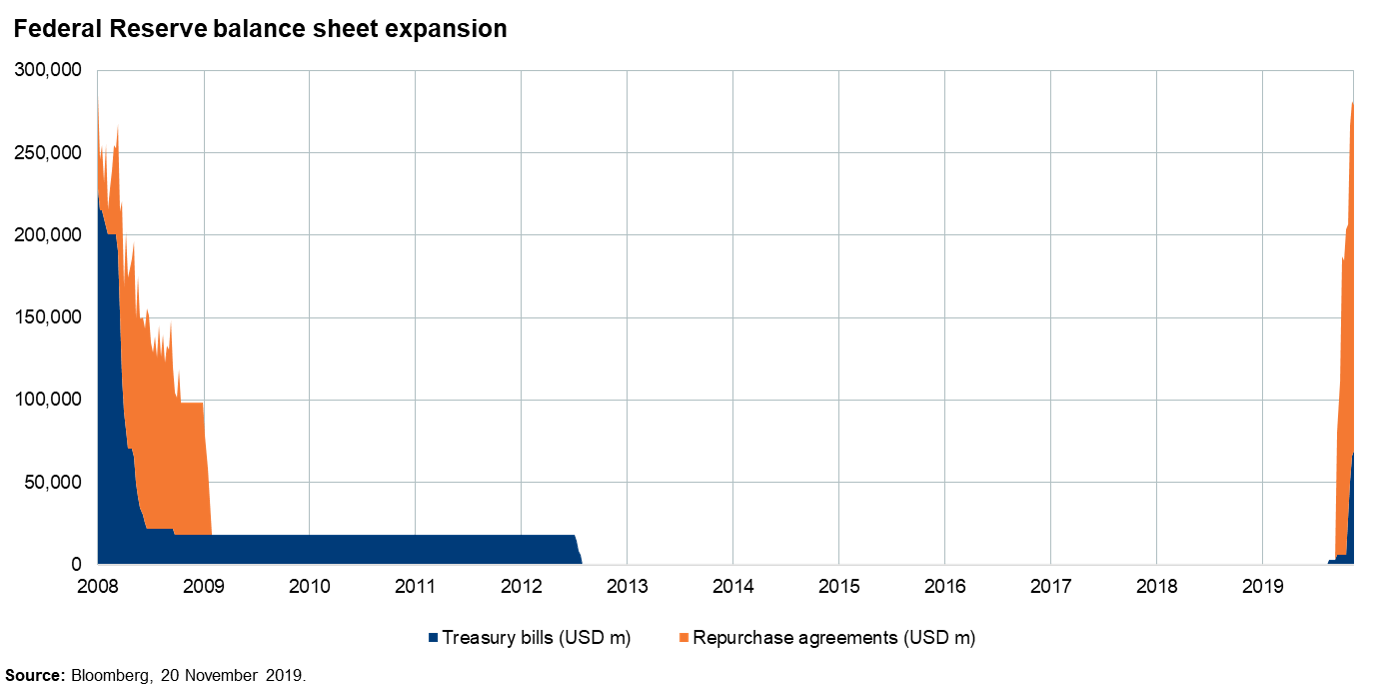

In response to this stress, the Fed launched a standing repurchase (repo) facility (allowing commercial banks to swap US Treasuries for reserves while still booking the US Treasuries as HQLA). Had this been done ahead of companies paying their taxes, it would have been likely to be enough to ensure there were ample reserves. However, it was not until mid- September that the Fed initiated this facility, by which time the damage had been done in the funding markets

Between the end of August and 20 November, the Fed’s repo facility increased from zero to $199bn (see the chart below). Alongside purchases of US Treasuries totalling $81bn, this created a combined intervention of $280bn, which had the net result of expanding the Fed’s balance sheet to absorb and offset the increase in the TGA. At the same time, however, commercial bank reserves stayed flat.

Repo facility is not QE…

If the Fed had not acted in this way, the size of its balance sheet would have remained unchanged, while commercial banks’ aggregate balance sheets (both reserves and deposit liabilities) would have shrunk by $270bn.

Instead, as a result of the Fed’s actions between the end of August and 20 November, its balance sheet increased by $270bn, but owing to payment of corporate taxes, bank reserves only rose by $25bn. In this sense, the Fed’s recent balance sheet expansion should not be thought of as QE.

Given the TGA is now at the Treasury’s target of around $400bn, the Fed’s balance-sheet expansion may have come to an end. Over the week to 20 November, the outstanding repo balance fell by $10bn while purchases of US Treasuries came in at $15bn – a net balance sheet expansion of $5bn, and much lower than when the Fed was acting to offset the impact of the TGA rebuild.

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments