We assess the UK’s current monetary and fiscal predicament and the prospects for the gilt market.

Key points

- Radical UK government policies which aimed to slash taxes to aid growth have been replaced by a renewed focus on fiscal discipline.

- Panic has subsided in the gilt market, but the perceived hit to credibility and confidence are longer lasting.

- Mortgage rates have yet to fall materially, remaining at almost double the rates they were at six months ago.

- The decision not to extend generalised energy price caps beyond the spring reduces the potential hole in the public finances, but higher implied future borrowing costs, on top of the hefty additional interest bill on index-linked gilts already incurred, still leaves a sizeable gap to fill.

- Should the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee press ahead with quantitative tightening (QT), and the chancellor plug the budget gap with fiscal restraint, it may mean fewer interest-rate rises.

- In our view, having reversed most of the sell-off since late September, gilt yields are not high enough to represent compelling value versus better-rated New Zealand, Australia and, to a lesser extent, US government bonds.

It has been a tumultuous few weeks for the United Kingdom, not least for the gilt market. As I wrote recently in a blog entitled The closest thing to crazy? in the aftermath of the not-so-mini budget in late September, that ill-fated fiscal statement contained what we believed to be many of the wrong policies and the wrong priorities at the wrong time.

The statement elicited a damning verdict from the financial markets, as well as in opinion polls, and it caused havoc for UK defined benefit pension schemes, necessitating emergency intervention from the Bank of England. As predicted in the blog, the authors of those seemingly ill-judged policies (Prime Minister Liz Truss and Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng) were both forced to resign.

New leadership

The UK now has a new prime minister and a new chancellor in Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt respectively. Radical policies which aimed to slash taxes to aid growth have been replaced by a renewed focus on fiscal discipline. Panic has subsided in the gilt market, but the perceived hit to credibility and confidence are longer lasting. Not least, mortgage rates have yet to fall materially, remaining at almost double the rates they were at six months ago. Recent data also suggests an understandable reluctance by consumers to buy big-ticket items.

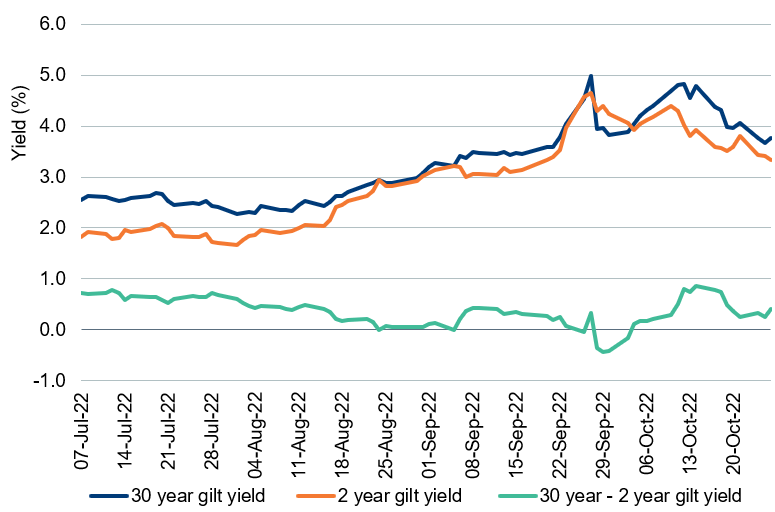

Gilt yields have retraced somewhat from the 5% peak seen in late September, but they remain materially higher than over the summer. Not only has the level of gilt yields remained volatile, but the curve shape has been very erratic, as the Bank of England plays ‘whack-a-mole’. The chart below shows the 2-year and 30-year gilt yield history since former Prime Minister Boris Johnson was forced to resign in early July.

UK gilt yields 7 July – 26 October 2022 (%)

Source: Bloomberg, 26 October 2022

Emergency intervention on financial-stability grounds in late September arrested the spike in long-term gilt yields which had been brought about by forced selling from the liability-driven investing (LDI) community and caused the curve to invert briefly. However, in the first half of October the curve re-steepened, before the budget measures were progressively reversed and the curve flattened again. The Bank of England’s decision to exclude any gilts dated 20 years or more from its plan to sell gilts for the remainder of 2022 also supported this flattening.

Rating downgrades

The decision not to extend generalised energy price caps beyond the spring reduces the potential hole in the public finances, but higher implied future borrowing costs, on top of the hefty additional interest bill on index-linked gilts already incurred, still leaves a sizeable gap to fill. Credit rating agency decisions to revise the outlook on the UK’s rating to negative over recent days reflect this.

See-sawing energy pricing policy also has implications for inflation; former Chancellor Sunak’s policy of allowing the market to set utility prices but paying rebates meant that headline inflation rose, at significant cost to the Exchequer in the form of higher interest and principal payments on index-linked gilts. Former Prime Minister Truss’ price capping pushed down headline inflation, but other policies threatened to push up core inflation. Assuming only targeted or partial help with energy bills beyond the spring, combined with tighter fiscal policy, we could expect higher headline inflation in the middle of next year, but lower underlying inflationary pressures, which could be a good environment for index-linked gilts, offering good carry from still-elevated retail price inflation, while real yields may drop as the economy sags.

It was noteworthy that under Truss and Kwarteng’s plan to borrow over £70bn extra this year, virtually nothing was allocated to additional index-linked gilt issuance, such is the sensitivity of these bonds to higher inflation. Even as financing needs abate, we would expect index-linked gilt supply to remain relatively low as a proportion of the total debt issuance, which may also offer technical support to that market, offset by uncertainty around future LDI-driven demand.

Plate spinning at the Bank of England

Meanwhile the Bank of England continues its plate spinning: raising interest rates to tackle inflation, selling corporate bonds and gilts (after false starts) as part of its quantitative tightening (QT), while standing ready to take additional measures if financial stability is threatened. Confirmation that the full fiscal statement and Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts will be delayed until 17 November, to allow time for the new prime minister and cabinet to fine-tune fiscal policy, only adds to the Bank’s headache, as the next interest-rate policy meeting is on 3 November.

We now know that the Bank of England had not been briefed about the disastrous ‘mini budget’ when it made its last rate decision the day before that event. We hope and expect that Bank officials will at least have been briefed on the outlines of fiscal plans before they make their next decision.

The delay to the fiscal update from 31 October to 17 November is perhaps understandable, but it has created a little more market volatility, albeit not on the scale of late September/early October, because the renewed commitment to fiscal responsibility seems non-negotiable for now.

Fewer rate rises ahead?

Should the Monetary Policy Committee press ahead with QT, and the chancellor plug the budget gap with fiscal restraint, it may mean fewer rate rises. This might help short-dated gilts but is unlikely to be supportive for sterling, already dogged by twin deficits and high inflation; however, it is already beaten up. Gilts may capture a bid on weakening economic growth, and long gilts are currently excluded from QT, providing some respite, but we would not base a long-term investment case on this temporary reprieve, especially when faced with uncertain demand from overseas investors and pension funds.

As gilt supply is still likely to outstrip demand, even as spending plans are reined in, and with political and social discord high, twin deficits, and the UK’s relations with the European Union still fraught, we expect volatility in sterling assets to remain high. In our opinion, having reversed most of the sell-off since late September, gilt yields are not high enough to represent compelling value versus better-rated New Zealand, Australia and, to a lesser extent, US government bonds.

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments